Part 3 of the “Gens de Couleur Libres” Series

We began this three-part series by exploring the origins and cultural identity of les gens de couleur libres, the free people of color in antebellum New Orleans. We then turned our attention to Rosette Rochon, a free woman of color and influential developer in the Faubourg Marigny.

In this final installment, we explore the life of André Martain Lamotte, a free man of color who built many of the homes that shaped this Creole neighborhood. A craftsman, contractor, and eventually self-described architect, Lamotte’s work and life offer a deeper understanding of how free people of color influenced the physical development of New Orleans.

Origins and Family Legacy

André Martain Lamotte was born on October 25, 1818. His parents were André Martin Lamotte, a white Haitian refugee, and Eugenie Fraissinet, a free woman of color. Lamotte’s name appears in various records under different spellings—Marstain Lamotte, Lamothe—but his legacy is unmistakable.

His father, like many white Creoles fleeing Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) during the revolution, struggled to protect his reputation in Louisiana. Lamotte Sr. famously published a newspaper rebuke in 1811, defending his family’s racial purity in response to rumors about ancestry among fellow refugees. He even obtained parish records from Les Cayes, Haiti, to document his lineage. Ironically, his son would become known not for his whiteness, but for his contributions as a free man of color in New Orleans.

Career and Social Status

Although Lamotte is listed as having “no profession” in the 1850 census, he appears as a builder in the 1851 city directory, and owned property valued at $11,000, including three enslaved individuals. Based on census analysis by Frank Lovato, Lamotte fell into the upper middle class among free people of color at the time. He did not reside in the wealthiest Creole enclaves but was still a man of means.

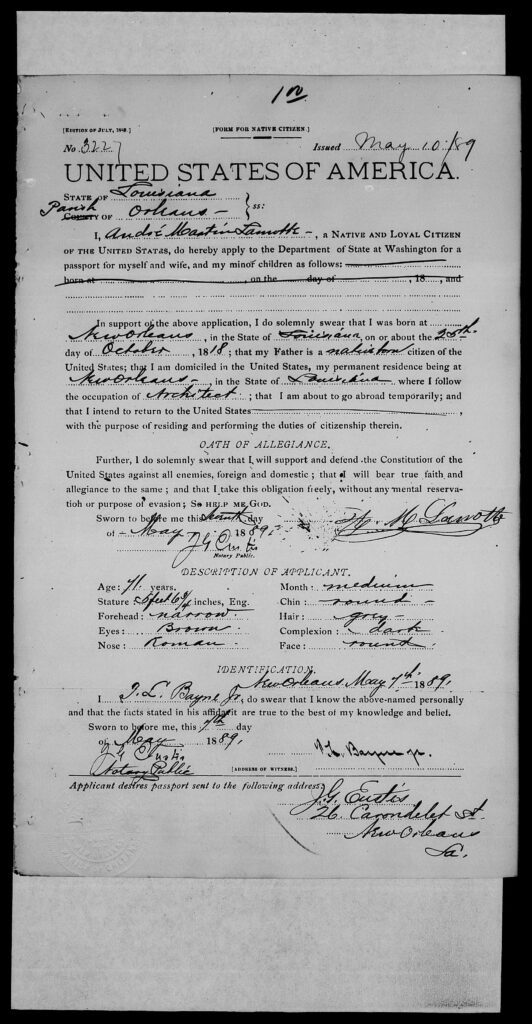

In his 1889 passport application, Lamotte referred to himself as an architect, a title not granted lightly at the time. The document describes him as five foot six, with a dark complexion, narrow forehead, brown eyes, a Roman nose, and a round face and chin. Whether formally trained or self-taught, Lamotte’s increasing confidence in calling himself an architect signals a shift in both status and skill.

Personal Life and Descendants

Lamotte is believed to have fathered at least seven children with three women: Emma Dupuis, Octavie St. Avide, and his enslaved partner, Catherine. His children with Emma were born between 1839 and 1846 and were listed as “colored” on official records. Those with Octavie, whom he married in 1891, were born between 1890 and 1892 and were recorded as “white.” His children with Catherine are not officially documented, though one son, Martin Lamotte, went on to serve in the Confederate army and later became a skilled bricklayer. Among Lamotte’s notable descendants is the legendary jazz musician Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe, better known as Jelly Roll Morton. His parents, Edward Lamothe and Louise Monette, both identified as Creole, trace their lineage back to André Lamotte and reflect the enduring legacy of this family within New Orleans’ cultural and artistic history.

Skilled Labor and Community Building

Craftsmanship was one of the few professions where free people of color could gain economic independence and social standing. Many, like Lamotte, worked as builders, plasterers, stone masons, and other artisans. These trades provided not just income, but also access to networks, apprenticeships, and generational skill-sharing.

In early New Orleans, the apprentice system allowed enslaved and free people of color to learn trades. Over time, this labor force became the backbone of construction in neighborhoods like the Faubourg Marigny and Treme. Builders of color often hired others within their community, creating an economic ecosystem rooted in resilience, expertise, and mutual support.

As Sybil Kein writes in Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Color:

“Builders distinguished themselves in the community of free blacks. Families like the Dollioles, the Fouchés, and the Lamottes amassed fortunes as contractors and builders of much of the outer French Quarter and the faubourgs or suburbs, Marigny and Treme.”

Architectural Contributions

Lamotte played an important role in the built environment of New Orleans’ early 19th-century neighborhoods. He is believed to have constructed many homes in the Faubourg Marigny, including several for Rosette Rochon. Among them was her home at 30 Union Street (now Touro Street), a two-story residence with a front-facing kitchen—a departure from traditional layouts where kitchens were housed in rear outbuildings.

Although historical records make it difficult to attribute specific surviving structures to Lamotte, his hand in the physical shaping of Creole enclaves is evident through oral histories, mortgage documents, and property transfers. Like Rochon, Lamotte’s legacy is tightly woven into the architectural and cultural fabric of New Orleans.

Final Years and Legacy

André Martain Lamotte died just after midnight on November 2, 1895, at the age of seventy-seven. Though many of the structures he built are lost to time or remain undocumented, his influence survives in the neighborhoods he helped construct.

Lamotte is remembered not only as a builder and architect, but as a man who navigated complex racial and class boundaries to leave a lasting impact on the city. His story illustrates the creative and economic agency of free people of color during a time of great constraint.

Continuing the Conversation

Although this marks the final entry in our current three-part Gens de Couleur Libres series, the stories of free people of color in New Orleans are far from complete. Their contributions to architecture, culture, and community form a legacy that still shapes our city today.

Future additions may explore other key figures, such as Joseph Chateau, known as “one of the most prolific free Black builders of the antebellum period.”